SAPATOS

by Pablo Bautista

“Sapatos” was the word that shattered my 11-year-old world. My siblings and I—all five of us—attended Catholic school in Visitation Valley, a working class neighborhood in the southeastern part of San Francisco where we also resided. The neighborhood in the late 70s and early 80s consisted of a mixture of African-Ameri- cans, first and second generation Irish-Americans and Italian-Americans, Samoans, and recent immigrants from the Philippines, China, and Mexico. The houses, built after WWII, butted up against one another, designed as though to support each other during earthquakes. Against the backdrop of the undulating brown folds of the San Bruno Mountain, Geneva Towers, the troubled twin 20-story high-rises synonymous with Section 8 housing, drug activities, and gun violence, loomed large over our neighbohood.

Having immigrated to the States from the Philippines four years prior, my siblings and I were still acclimat- ing to the fact that we were no longer a member of the ethnic majority. As a consolation, however, we weren’t the only minorities in our school in Viz Valley (the locals’ nickname for our district). During roll calls in school, we were exposed to different ethnic names—the Uus, the Freemans, the Toussaints, the Reyeses, the Horanzys, the Looneys, the Perrados, the Relojos, the Maldenados, the Leongs, the Aliotos, the Pecks, the Oreganos.

Although not all of my classmates were Catholic—their parents knew better than to enroll their children in the notoriously dangerous public schools—we Filipinos were devout practitioners of the religion. In fact, when I became an altar boy, my parents beamed with pride whenever they saw me serving mass, donning my black and white altar boy cassock, ringing the bells, holding the communion plate under the chins of the communicants. Back then, only boys could serve at the altar. It was through school that I became involved with Legion of Mary, “A Catholic organization working world wide to bring Jesus and Mary to the people of every country.” I wasn’t really sure what the agenda of the organization was, but if my full-time working parents didn’t object, then why should I? During one summer every Saturday morning, several classmates and I would converge at our church and cram into the two-door Nova sedan of Sister Madeline, a silver-haired unmarried layperson who was addicted to nicotine. Although she wasn’t a nun, we kids had to call her Sister Madeline. Sister Madeline would drive us to convalescent homes in Daly City where we, mostly children of color, would bring cheer and breathe of life to the dreary and lonely existence of the elderly Caucasian patients. Sister Madeline’s car had bench seats and a long seat belt that went over our laps. When I sat in the front with her, I noticed the car’s ashtray overflowing with cigarette butts. Behind her pointy black cat-eye glasses, Sister Madeline’s gentle green eyes would soften and apologize for her addiction and then warned me never to smoke. I reassured her that I wouldn’t because it’s disgusting, unhealthy, and it stinks. In high school when I was rolling my own cigarettes, never once did her warning cross my mind.

At the convalescent home, we children would encounter a world of narrow fluorescent-lit hallways littered with old hunched-backed creatures in wheelchairs or walkers, mumbling “I don’t know what to do, I don’t know what to do” on repeat. A whiff of urine would hit us at every turn.

After one visit, some of my classmates never returned to the convalescent homes in fear of getting mauled by a demented senior foaming at the mouth. I didn’t mind because I knew I could outrun these old folks. Plus I was a goody-two shoes and an altar boy, so I felt extra protection from Mary and Jesus. After one of our visits, as we waited outside for Sister Madeline to take us back, I participated in an obnoxious game of talking about people to their faces in Tagalog. It was called “capping” in my day. For example, “Your momma is so fat she has her own zip code” is a cap. I was speaking Tagalog with another Filipino classmate in front of two Spanish-speaking classmates. I mentioned how ugly the shoes of the Spanish-speaking female classmate of ours. “Ang pangit nang kanyang sapatos!” As we chuckled, she immediately confronted me. “Why are you talking about my shoes?” I was flabbergasted. I didn’t know she understood Tagalog. With an air of superiority, she informed me that “sapatos” was in fact a Spanish word (zapatos) and not Tagalog. On the ride home, I sat in the back seat, hurting from the realization that words I took for Tagalog, as my own native language, were in fact, not mine. What I thought was mine became foreign to me. I felt betrayed by the world for not telling me this. As I rattled off a list of other words that I thought were Tagalog—kutsara (spoon), mantikilya (butter), pantalon (pants), lamesa (table), Bautista—I began to see myself and the world around me in a new light.

When I returned home, I asked my mom to list all the Tagalog words she knew for “shoes.” And I jotted them all down, for next time.

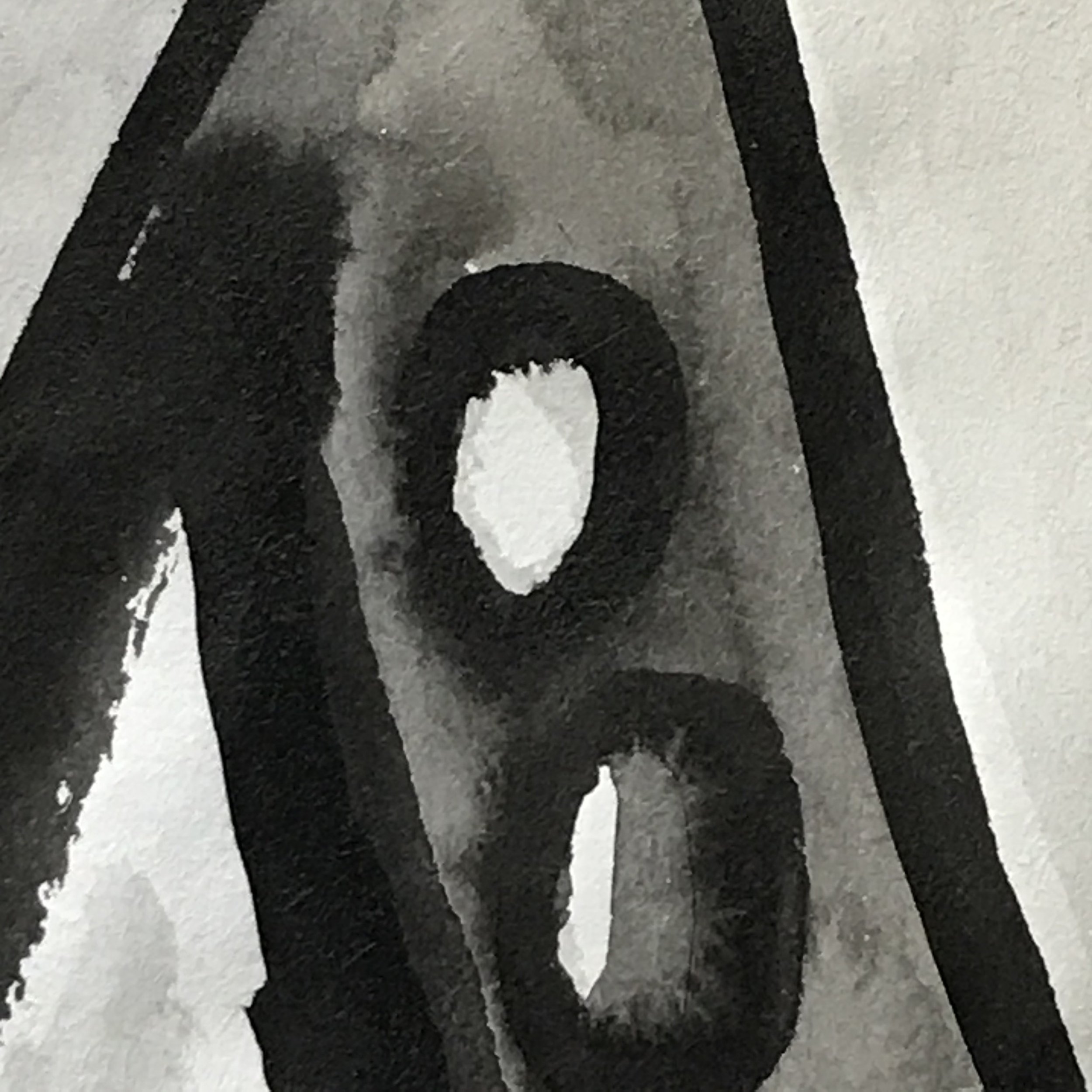

Untitled

watercolor

r.a.d. Leng Leng